Sri Lanka’s Ancient Ayurvedic Health Care System Evidence from the Past

Today, health care systems are often mistakenly viewed as a modern invention of Western civilizations. But the study of Sri Lanka’s past shows that this is not so, and that Ayurvedic medicine was central and widely practiced under the patronage of Sri Lankan kings.

In fact, the layouts of five ancient hospital complexes in Sri Lanka, ancient inscriptions, and the chronicles of Sri Lanka, are evidence that shed new light on our understanding of ancient medicine and health care system of Sri Lanka.

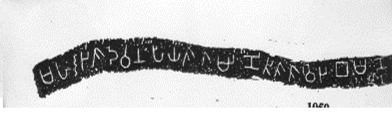

Evidence for physicians from Brahmi Inscriptions

The evidence of physicians who lived before the common era in Sri Lanka is found in Brahmi inscriptions, that were carved on the surface of caves where Buddhist monks resided between 3rd Century B.C.E to 2nd Century C.E. The below two inscriptions give us information about physicians.

- An inscription by the name of Piccaṇḍiyāva (2nd Century B.C.E.) gives evidence of king Maharajaha Devanapiya’s physician by the name of Gobuti.

- Information of a physician called Mitaha, is also found in the Rājaṅgaṇē inscription (2nd Century B.C.E): “upaska veja Mitaha puta Miṭigabutiya leṇe”.

Kings who patronized the development and evolution of medical tradition in Sri Lanka

The development of medicine in Sri Lanka owes much to the kings. Several of them ordered the construction of hospitals and encouraged health care.

Evidence of hospitals in the fifth century B.C.E

The Mahāvaṃsa, the great historical chronicle of Sri Lanka, gives evidence of sivikāśālā (a hall where the śivalinga was deposited or a convalescence home) and sotthiśālā (hall that Brahmins used for chanting or a hospital) during the reign of king Paṇḍukābhaya (437-367 B.C.E). According to the commentary of the Mahāvaṃsa, Mahāvaṃsatīka, two illustrations are given of a sivikāśālā and a sotthiśālā. If the above given fact is true, it should be noted that there were separated halls for treatments even in the 5th B.C.E.

The preservation of dead bodies

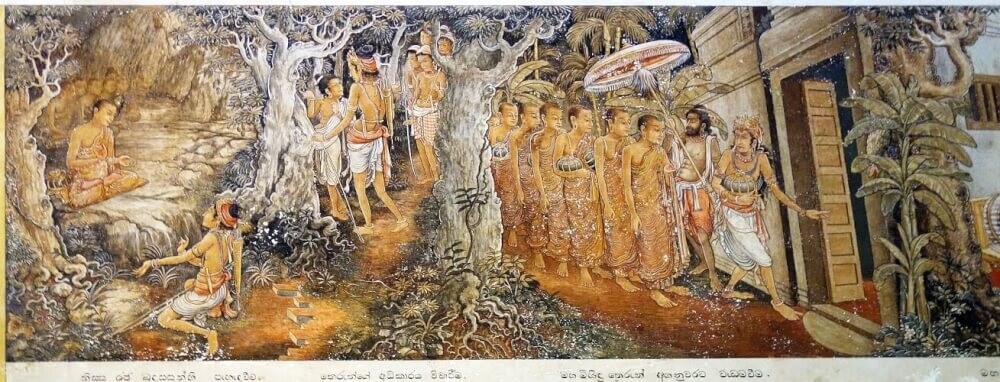

The preservation of corpses has long been known in the Indian ocean. “Mahinda thera”, the son of Emperor Aśoka, who introduced Buddhism to Sri Lanka died during the rule of King Uttiya (5th century B.C.E.). According to the Mahāvaṃsa, his dead body was preserved with treatment.

King Uttiya had made arrangements to lay the dead body in a golden chest sprinkled with fragrant oil, and the well-closed chest was laid upon a golden, adorned bier. The king commanded solemn ceremonies. The chest was brought to the Mahāvihāra (the main temple). The king then commanded diverse offerings throughout the week.

Care for patients and animals

During the battle between Indian King Elara and Sri Lankan king Dutugämuṇu (161-137 B.C.E), an elephant called Kaṇḍula was injured by the balls of red-hot iron and molten pitch.

It was further recorded that the injured elephant was treated by physicians. The Mahāvaṃsa states, “The elephant was covered with a cloth and had put its armor on it and had bound upon its skin a seven times folded buffalo hide and above it had laid a hide steeped in oil, and set it free”.

Financing and organizing the health care system

King Wasabha (65-109 C.E) facilitated the payment of a wage (gilan vetup) to the poor as well as to the sick Bhikkus (monks).

King Buddhadāsa (340-368 C. E) set up hospitals in every village on the island. He made a summary of the essential content of all the medical textbooks and compiled a book called Sārārtasangraha and distributed it among the physicians in Sri Lanka for the betterment of the future physicians. He appointed physicians for ten villages each. He gave salaries to physicians from the income derived from the paddy fields. He also appointed physicians for elephants, horses, and soldiers.

King Buddhadāsa built shelters for cripples and the blind in various places. Mahāvaṃsa gives further information about his great pity. He had a pocket in his mantel where his knife was enclosed. He used to use this knife to relieve anyone affected by pain. The king healed physical and spiritual diseases.

King Buddhadāsa was a renowned physician. He treated a snake stricken with a stomach disease, a Bhikkhu (a Buddhist monk) who had consumed milk with worms, a horse who was afflicted with hemorrhage, a man who had swallowed the egg of a water snake, a Caṇḍala woman (a woman of low caste) whose womb had taken a wrong position seven times with child, a Bhikkhu disturbed in his exercises by a writhing disease, a young man who drank water with frog eggs, and a man who often doubted the monarch.

Outstanding achievements of various kings in terms of healthcare

As we have seen, many kings have marked the history of Sri Lanka by organizing the health system. Here are some other notable rulers that can be found in historical sources.

- King Mahānāma (410-432 C.E) built refuges for the sick.

- King Datusena (459-477 C.E) constructed halls for cripples and people who suffered from diseases.

- King Silākāla (518-531 C.E) expanded the treasure allocated for the maintenance of hospitals.

- King Agbō VII (754-760 C.E) treated the sick.

- King Udaya I (780-785 C.E) built hospitals both in Polonnaruwa (an ancient capital city in Sri Lanka) and Paṇḍāviya (a town in the dry zone of Sri Lanka); the income received from the village was donated to those hospitals. He also constructed halls for the cripples.

- King Sēna I (819-839 C.E) constructed a hospital to the west of the capital.

- King Sēna II (839-874 C.E) constructed a hospital at Chētiyagiriya (a town in the dry zone of Sri Lanka).

- King Kassapa IV (898-914 C.E) built hospitals in Anurādhapura (an ancient capital city of Sri Lanka) and Polonnaruwa for combating the Upasagga disease. He also built medical halls in many towns.

- King Kassapa V (902-912 C.E.) built a hospital in the city and endowed the villages with medical facilities.

- King Parakkramabāhu I (1153-1186 C.E) built a great hall for many hundreds of sick people where each sick person was attended to by a special slave. As required, a female slave was occupied preparing medicine, food, and liquid both during the day and night. The king appointed the physicians. Healing activities were tested daily. The king treated a crow suffering from an ulcer that had formed in its cheek.

Ruins of ancient hospitals in Sri Lanka

Throughout Sri Lanka, there are many remnants of ancient hospitals that attest to the islanders” interest in medicine. These ruins bear witness to highly regulated practices.

The hospital complex at Thūpārāma

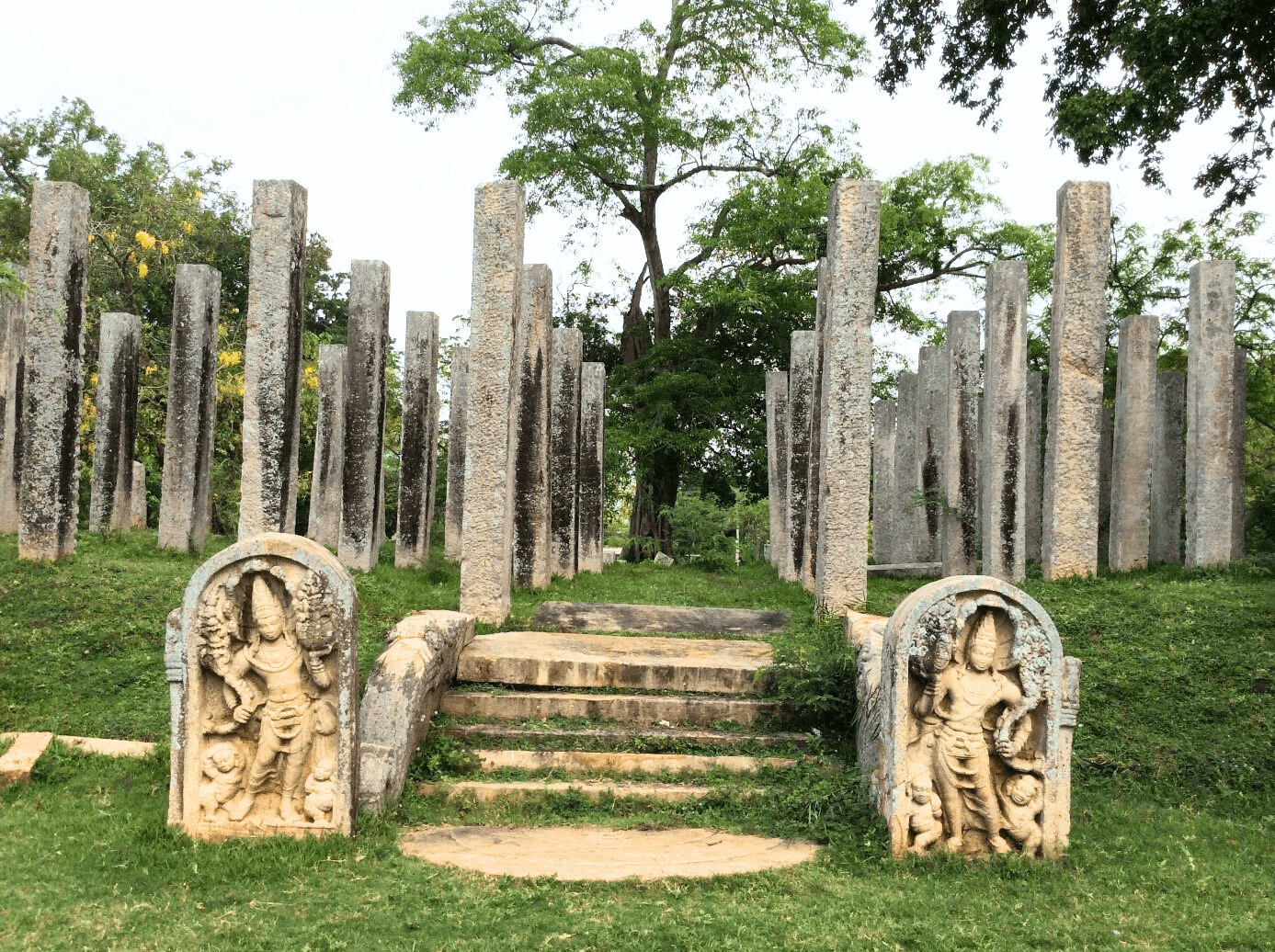

The Thūpārāma hospital complex was situated near the Thūpārāma dāgäba in Anurādhapura. The site was excavated by H.C.P Bell and the entrance is yet to be identified. The rooms for the patients may have been arranged around the shrine room as in the Mihintalē hospital Complex (near Minhintale town in modern Sri Lanka). The shrine room is considerably big in size. The guard stones as well as moonstones, can be identified.

The hospital might have been built before the 8th century C.E. and was probably in good maintenance during the following century. The Kiribathvehera pillar inscription shed light on the endowment given to this hospital by king Kaśyapa IV.

The hospital complex in front of the Ruwanwälisäya

This hospital is located in the Anurādhapura district, just in front of the Ruwanwälisäya (a major stupa). Half of the complex is buried under the road that leads to the Sri Mahābodi from Ruwanwälisäya. The Sri Mahābodi is the sacred bodhi tree shrine; the bodhi tree is a sapling of the sacred bodhi tree in India, under which the Buddha attained Enlightenment; it is considered as the oldest historical tree in the world.

The Hospital complex at Mihintalē

The ruins of the Mihintalē hospital are scattered near the Chēthiyagiriya mountain in the Anuradhapura district. As recorded in the Mahāvaṃsa King Sēna II (839-874 C.E) constructed a hospital at Chētiyagiriya. Thirty-one rooms have been identified.

All the rooms are arranged on a high platform. The distinctive features of this hospital complex are a consulting room, a room for the hot water bath, an outer court, an inner verandah, a courtyard, a shrine room, and a room for the medicinal trough.

The hospital complex at Mädirigiriya

The Mädirigiriya hospital is situated in the Tamankaduwa area about forty-six miles to the South East of Anurādhapura. The Hospital can be dated to the 8th and 9th centuries C.E. A pillar inscription that belonged to king Kassapa V testifies that there was a hospital complex there. The inscription orders that the dead goats and fowls should be given to the hospital attached to the Buddhist temple.

The hospital complex at Ālāhanapirvena in Polonnaruwa

This is located 120 m away from the Rankotvehera Dāgäba, a major stupa in Polonnaruwa. As mentioned in the Cūlavaṃsa (another historical record of the monarchs of Sri Lanka) this hospital complex had been constructed by King Parakkramabahu I (1153-1186 C.E). It was small in size and there was a separate room for the medicinal trough.

Having the lavatory inside the building was an important feature. Medical equipment used for operations, such as scissors were found at the site. These medical equipments are very similar to that used today.

The hospital complex at Digavāpi

The proper excavation has not so far been done at Digavāpi, a Buddhist sacred shrine and an archaeological site in the Ampara District of Sri Lanka. The medicinal trough and numerous other items are exhibited at the museum in Digavāpi.

Conclusion

Ayurvedic medicine, still present in modern Sri Lanka, is the result of centuries of medical tradition. The existence of accurate and quality hospitals, doctors and medical procedures demonstrates that the country has recognized the importance of an elaborate health care system since ancient times.

Author: Prof. Nadeesha Gunawardana

Editor: Izold Guégan

Discover the fascinating history of Sri Lanka through our articles dedicated to the Pearl of the Indian Ocean!

Sources

CūĪavaṃsa 1928 Gieger Wilhelm (trans.), Asian Educational Services, New Delhi.

Epigraphia Zeylanica 1984 (ed.), Saddhamangala Karunaratne., vol. vii, Archaeological Survey of Ceylon.

Inscriptions of Ceylon 1970 S. Paranavithāna., Archaeological Survey of Ceylon.

The Mahāvaṃsa or the Great Chronicle of Ceylon 1950 W. Geiger, Ceylon Government Information Department, Colombo.

Vaṃsatthappakāsinī commentary on the Mahāvaṃsa 1977, Malalasekara (edit.), the Pali text society, London.

Ilangasinghe Mangala 2007 Savistara Mahāvaṃsa Anuvādaya, Godage publishers, Maradana.

Neel Kiriella 2017, Me Ape Urumayayi, Ilupitiy Ranjith (trans.) 18-22, Cultural Department, Sri Lanka.

Majumdar S.M & Mukherjee N Y 2013, Essays on History of Medicine, IIRNS publications Pvt. Ltd, Mumbai.

Vijeratna Gunasiri D.P.D 2010 “Ayurveda Shalvidya vidyave Ithihasaya Saha Sri Lankave pärani shalyavidya Upakarana”, Prashantha Perera (edit) Essays on Archaeology, History, Buddhist Studies & Anthropology, Festschrift for Professor S. B. Hettiaratchi, Sarasavi publishers, 141-160pp.